Positive sustainable impact requires strong partnerships between permanent institutions in the client country and outside development actors. The achievements of time-bound programs that do not partner well with local permanent institutions dissipate quickly after a program closes. Sustainable impact comes from permanent local institutions adopting, in some form, the changes promoted by the development program. Two problems have hindered successful partnerships:

The first problem is that outside actors tend to measure the capacity of local institutions, but local actors are not invited to formally assess the outside organization that has come to partner with them. But it is clear that the quality of a partnership comes from both actors. In order to assess and improve a partnership, it is necessary to assess both partners. Local actors are able to give plenty of insightful feedback, informally, when invited. Thus, the first solution is to measure the partnering capacity of both local and foreign actors.

The second problem is that there have been few assessment instruments that can be quickly and easily used by both parties, and that can be used for real-time feedback.

Systemically, one underlying problem is measurement. Development programs seldom set goals for monitoring and evaluation (m&e) indicators for measuring the strength and effectiveness of the program’s partnerships. This state of affairs is in part due to weaknesses in current measures for partnerships. Current measures tend to be checklists based on what we believe to be desirable traits in partnerships. However, these checklists do not measure the developmental state of the partnership, or indicate its effectiveness.

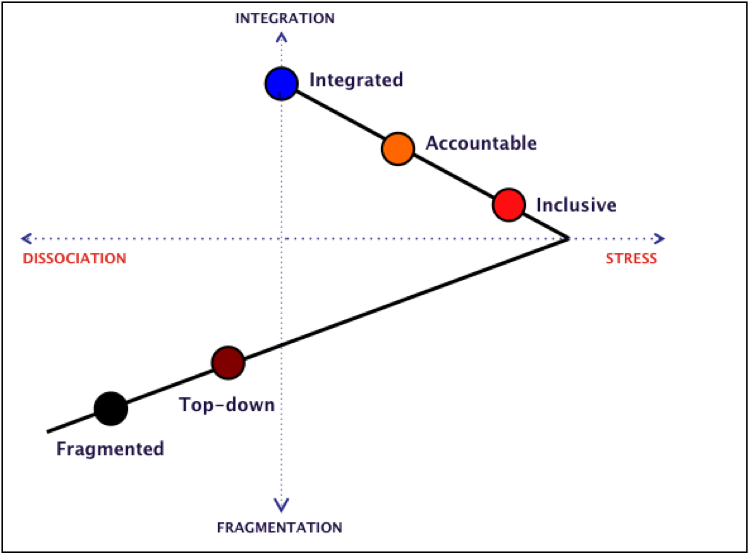

CCP’s work is based on 28 years of research and experience by Eric Wolterstorff and The Wolterstorff Group (TWG). The model developed by TWG shows that partnerships fall into five stable Cooperative States based on levels of cooperation, and that each state is a measurable, albeit coarse, indicator of a partnership’s performance. The five cooperative states are:

- Integrated

- Accountable

- Inclusive

- Top-down

- Fragmented

TWG’s work identified a clear relationship between performance and cooperation. When cooperation increases from one state to the next, the performance of a partnership, as defined by stakeholders, more than doubles. Conversely, if cooperation decreases, and the partnership falls to a lower state, performance drops drastically.

The model also shows that each state has a characteristic grouping of organizational elements. This allows CCP to create a Partnership Maturity Matrix that helps not only to identify the cooperative state, but to identify the steps necessary to improve cooperation in a partnership. Moving from one state to the next is straightforward, though often difficult. It requires developing a number of a partnership’s concrete organizational elements to match the characteristic of the next highest state. This concrete developmental clarity allows CCP to help its clients to identify the priority interventions that will most effectively and efficiently increase performance.

The following describes in more detail the CCP model as an indicator for partnership effectiveness, and as a methodology to prioritize organization development interventions.

The Five Cooperative States

The Five Cooperative State Model, graphed below, shows the relationship between stress and cooperation (with cooperation as the proxy for performance). The vertical axis measures cooperative capacity, from minimal cooperation – fragmentation – to the highest level of cooperation – integration. The horizontal axis measures stress, from disassociation (the avoidance of feeling high levels of stress by not caring), to high feelings of stress. The attractor states, or Cooperative States, are shown by the colored circles. The names of the Cooperative States are general descriptions of the style of partnership in each state. The least cooperative and lowest performing partnerships are in the Fragmented State, and the most cooperative, highest performing partnerships are in the Integrated State.

Cooperative States As Indicators For Partnerships

As leading indicators, the Cooperative States broadly predict the results that will be achieved by a partnership in a certain state. Below, each state and expected performance is described. Under each heading, a general description of the state is listed. Below each list, the level of results that will be achieved is described.

Fragmented: Few outputs are achieved; no commitment to the partnership; no sustainability

Partnerships in the Fragmented State are unable to meet their deliverables. In the Fragmented State:

- There is a lack shared vision, mission, or exit strategy within the partnership

- Resource commitment is ad-hoc

- Leadership and an agreed-upon decision-making mechanism are not well defined, or are contested

- Management and communication systems are ad-hoc

- Knowledge is held informally and scattered throughout the partnership

- M&E is disorganized and measurements are ad-hoc

- There is a culture of intentional or unintentional sabotage

- Stakeholders are unclear of mission and dissatisfied with implementation

Fragmented partnerships have very poor performance; they face the likelihood of micro-management from their stakeholders and eventually break up because there are no benefits for any of the partners to continue.

Top-down: Most outputs are achieved; one dominant partner; very low likelihood for sustainability

Partnerships in the Top-down State are potentially able to generate outcomes to a minimum acceptable standard, but have low potential for sustainable impacts if the dominant partner withdraws from the partnership. In the Top-down State:

- There is one dominant partner

- Mission, vision, and exit strategy are held by the dominant partner and uncontested by the other partner(s)

- There is asymmetrical sharing of resources

- Management systems are defined, usually by the dominant partner

- Communication flows are one way, from the dominant partner to the others. Feedback from the other partners is not heard by the dominant partner

- There is a culture of risk aversion, safety, and ‘do my job’ – staff have no drive to do more than the minimum

- Stakeholders understand mission and vision, but feel ignored by the implementation process

- M&E is organized; measurements are of tasks performed.

While partnerships in the Top-down State may achieve their planned-for outputs, they are dependent on the dominant partner (almost always the outside partner). These partnerships are neither flexible nor responsive; moreover, they are not able to generate the enthusiasm and readiness on the part of non-dominant partners to take up ownership of the partnership’s program.

Inclusive: Most outputs and some outcomes are achieved; power is shared, often asymmetrically; inefficient, but with potential for real sustainability

Partnerships in the Inclusive state are able to achieve most planned outputs and some outcomes. In the Inclusive state:

- Power is shared, often asymmetrically

- Strategic goals and exit strategy are shared and aligned with the vision and mission

- There is substantial (enough to feel it, but not hurt) investment of resources from both partners

- Partners listen and respond to each other

- Management systems are transitioning to be inclusive

- Members have access to information in a disorganized manner; information flows both up and down

- There is a culture of loyalty, hard work, and complaint

- M&E is disorganized; measurements are of results

Partnerships in the Inclusive state should exceed minimum planned deliverables and outputs. These partnerships, due to the development of two-way communications, become more flexible and responsive. Their culture of shared power and resources greatly increases the likelihood that the activities or services implemented by the partnership can be sustained in some form if and when one partner withdraws from the partnership.

Accountable: Most outputs and outcomes are achieved; impact is probable; power and decision making are shared; high potential for sustainability

Partnerships in the Accountable state will meet or exceed high levels of deliverables. In the Accountable state:

- Power and decision making are shared

- Strategic goals, exit strategy, and action plans are shared and prioritized

- Both partners invest substantial resources into the partnership

- The partnership is able to prioritize and say ‘no’ to lesser priorities

- Management systems promote and enable prioritization within silos

- Within silos, cross-communication and access to information is as needed

- Stakeholders participate in the design and implementation of action plans

- M&E is organized; measurements are of results

Partnerships in the Accountable state should, given the resources available, achieve high levels of performance. Work within the partnership will be ‘siloed’. Within the silos, resources (budget, personnel, materials) are allocated efficiently in line with priorities. Each of the silos is flexible, responsive, and capable of implementing its activities, increasing likelihood of sustainable program delivery and sustained impacts.

Integrated: Maximum deliverables achieved; power is shared; greatest capacity for innovation and sustainable results across all aspects of the partnership

Partnerships in the Integrated State achieve the highest ideals of partnership. Shared power, shared investment of resources, and communication and management systems promote and enable prioritization and effective resource allocation across the partnership. This enables the rational and effective implementation of exit strategies leading to realistic sustainable delivery of program services and impact. In the Integrated State, the silo walls of the Accountable State are removed, and:

- Strategic goals, exit strategies, and action plans are shared and prioritized across silos

- Leadership promotes fully integrated partnerships and sustainable impacts

- Management systems promote and enable prioritization across silos

- Everyone in the partnership has access to information they need to make timely decisions

- Across silos, cross-communication and access to information is as needed

- There is a culture of rationality, teamwork, mutual trust, and mutual respect

- M&E is organized; measurements are of results

Partnerships in the Integrated state prioritize and use available resources optimally, resulting in the highest level of deliverables. The free flow of communication and ability to share resources across all levels of the partnership result in more effective adaptation of activities, approaches, and rational, effective exit strategies.

The identification of the state of partnership is a leading indicator; the state of the partnership shows us the current and, if the cooperative state does not change, the future level of effectiveness and productivity of the partnership. This allows partners and donors to set goals for, and measure the progress toward, the development of the stronger partnerships that are vital for the success and sustainability of their programs.

The identification of the Cooperative State of the partnership is also the starting point for the development of strategies and action plans for improving partnership performance. By incorporating a set of simple rules, partnership managers can establish strategies for strengthening their partnerships. Working with the maturity matrix (introduced below), they can develop and implement partnership-strengthening action plans.

Simple Rules For Strengthening Partnerships

The research by TWG shows that a small number of simple rules result from the model. These simple rules help guide leaders, managers, and consultants to develop plans to improve a partnership’s Cooperative Capacity. The first and foremost of these rules is that a program can shift, up or down, only one state at time.

Partnerships and programs can only shift one state at a time

Each state serves as a foundation for the next higher state. For example, a partnership cannot move from Fragmented to Inclusive directly. Trying to create inclusiveness without the clear vision and mission, strong leadership, and established systems and processes of a top-down program will not work; without the structure created in the Top-down State, the organizational foundation needed to invite participation and ownership from all staff of the partnership is absent. Similarly, a partnership cannot move from the disorganization of the Inclusive State straight to being fully Integrated without learning to measure results and prioritize resource allocation, which are the hallmarks of the Accountable State.

Conversely, if stress or crisis is fragmenting a partnership, the partnership will move down the states one at a time. For example, if an Integrated partnership team experiences more stress than it can manage, its members will fall back into a ‘hero’ mode in order to solve the issue confronting them. This recreates the siloed aspect to the Accountable state. If stress continues, the partnership members will grow extremely frustrated, lose coherence, and fall into loyal complaining, which characterizes the Inclusive State. Finally, continued stress will result in disassociation, as partners will acquiesce to a dominant partner and then eventually leave the partnership.

A partnership can only reach the cooperative capacity level of the partner with the lowest program cooperative capacity level

All partnerships are limited by the capacities of the partners. The partner in the lowest state will not be able to implement the systems, practices, and culture required for the partnership to be in a higher state. For example, a partner in the Top-down State will not be able to implement the bottom-up communication and shared responsibility required in the Inclusive State. Likewise, a partner in the Inclusive State will not be able to prioritize, a key requirement for moving to the Accountable State. Unless the partner in the lowest cooperative state can move itself into a higher state, the highest state attainable by the partnership is that of the lower state, even if the other partner functions in a higher state.

Each partner’s greatest leverage for strengthening the partnership is over itself

Each partner’s greatest opportunity to strengthen any partnership is to build its own cooperative capacity. Each partner has more direct control over its own internal systems, processes, and culture than over those of the partnership, or its partners. A program can most easily and quickly increase its own cooperative capacity and effectiveness.

The next best leverage point is to improve the cooperative capacity of the partnership. This is only possible when the cooperative capacity of the partnership is lower than the cooperative capacity of the partners.

The most difficult leverage point for strengthening a partnership is to help a partner increase its cooperative capacity. This is necessary when the cooperative capacity of the partnership is the same as the cooperative capacity of the other partner. Increasing the cooperative capacity of another organization, to have any chance of success, requires agreement, time, and a steady commitment of effort and resources from that organization.

Control the rate of change

Finally, change increases stress, which decreases collaboration. Efforts that introduce too much change too fast will lead to levels of stress that will defeat the effort to build cooperative capacity. The ceiling for the speed of change efforts can be easily and quickly measured with the cooperative capacity map.

Steps For Strengthening Partnerships

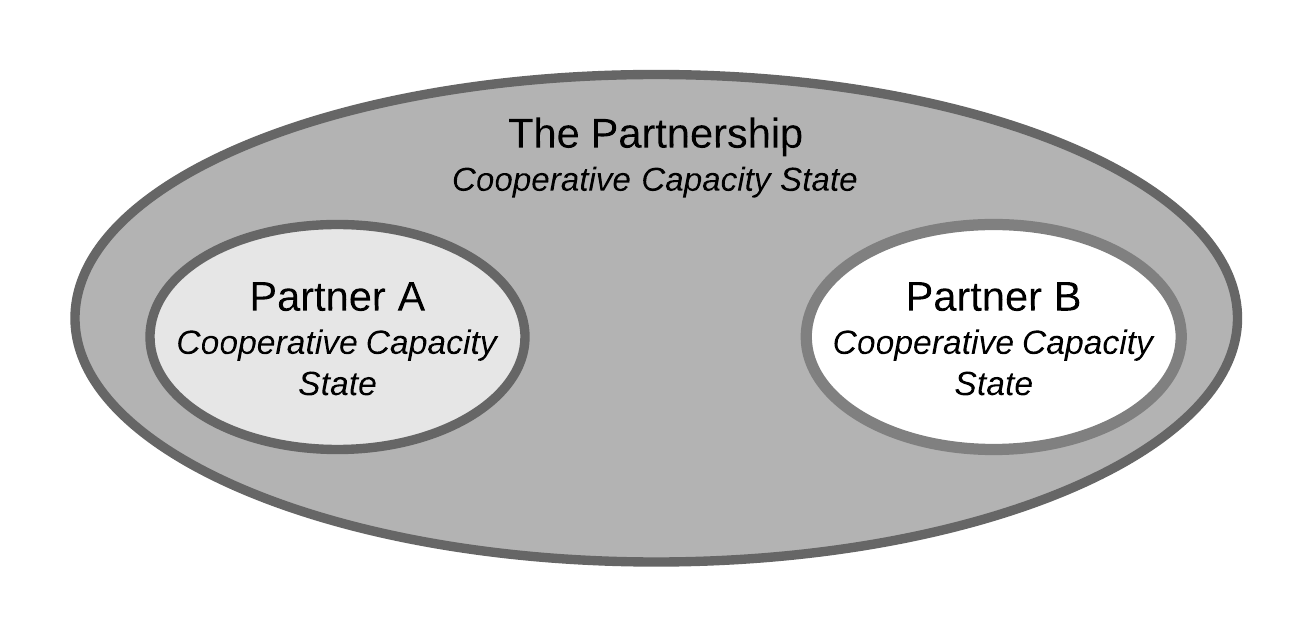

With these simple rules, partnership managers can develop strategies for strengthening their partnerships. Below is a simple, generic map of a two-member partnership:

CCP has developed a five-step process to assess and prioritize actions to strengthen a partnership.

Step one: Assess the cooperative capacity of both partners (Assessing Partners).

Step two: Assess the cooperative capacity of the partnership (see below).

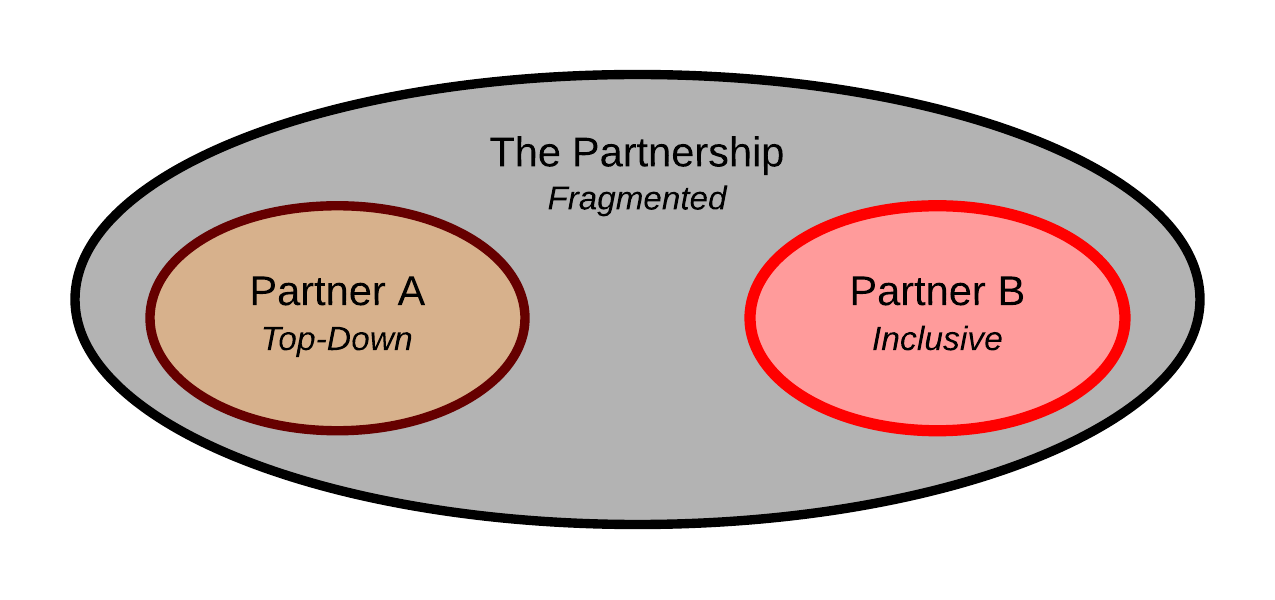

This graphic below is an example of a possible result of these assessments, showing one partner in Top-down (brown circle), one in Inclusive (red circle), and the partnership in Fragmented (black circle).

Step three: Identify all possible moves to the next higher state.

In a simple two-member partnership, there could be at most three possible moves: improve partner A, improve partner B, and improve the partnership. The latter is only possible when the cooperative capacity state of the partnership is lower than the cooperative capacity states of both partners.

If the cooperative capacity state of the partnership is the same as the lowest partner’s cooperative capacity state, there would only be two possible movements: the increase of the cooperative capacity state of one or the other of the partners.

Step four: Prioritize possible movements, based on:

- Best leverage (see the Simple Rules, above)

- Available champions

- Existing blockers

- Available resources

- Current dependencies

- Other constraints

Step five: Implement the highest priority movement.

The outcome of this process is a strategy to improve the partnership. In this example of the graphic above, the strategy would very probably be to:

- Move the partnership from Fragmented to Top-down

- Move partner A from Top-down to Inclusive

- Move the partnership into Inclusive

The process of moving a partner to the next cooperative capacity state is described in Assessing Partners. The process for building the cooperative capacity of the partnership is described below.

The Partnership Maturity Matrix: Moving To The Next Higher State

Holistic Analysis – Six Pillars and Five States

Many capacity building and partnership development efforts take a holistic approach to diagnosis and determining action. Holistic approaches normally assess elements such as alignment of the partner’s goals and culture, the partnership structure, power sharing and decision-making, role definition, and communications. Much of the development literature on assessing partnerships focuses on choosing partners and managing partnerships based on sets of principles of partnerships.

CCP takes a slightly different approach to the assessment and diagnosis of partnerships. CCP’s approach treats partnerships as a form of organization or team. In analyzing partnerships as a form of organization, TWG found that groupings of partnership and organizational elements are unique for each cooperative state. For example, the level of integration of mission and vision are distinctly different for each state; systems and procedures that are in place and effective are unique from state to state; communication patterns and other partnership/organizational elements are unique from state to state.

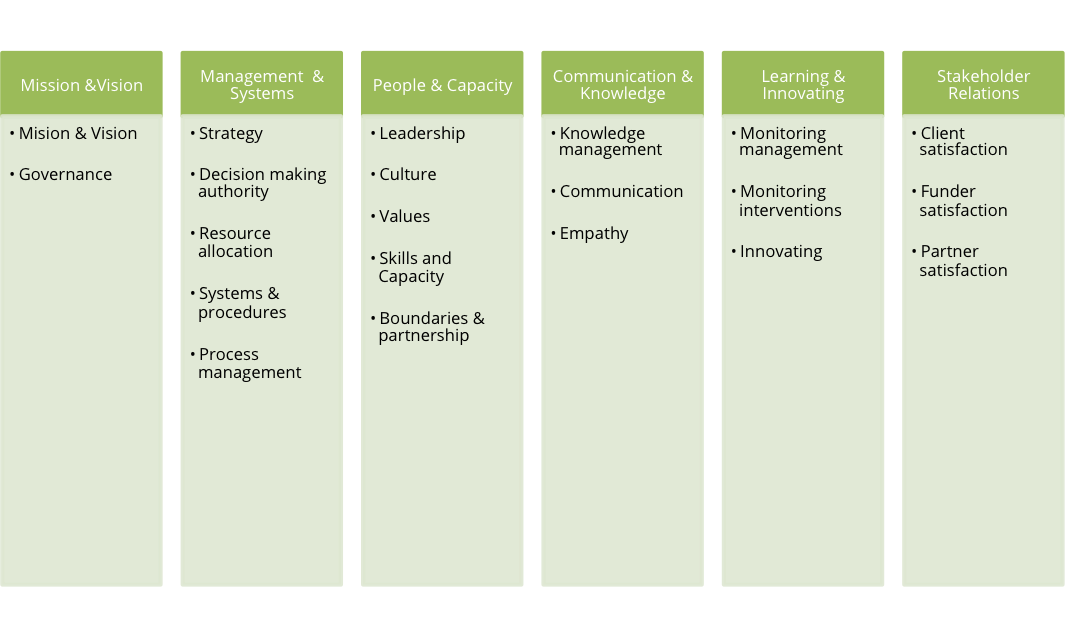

CCP organizes these elements into six pillars: 1) mission and vision, 2) management and systems, 3) people and capacity, 4) communication and knowledge, 5) learning and innovation, and 6) stakeholder relations. The graphic below shows each of the pillars with their components.

The fact that these pillars have unique characteristics in each state has two implications. The first is that CCP can precisely identify the state of a partnership by assessing the pillars. The second is that, since a partnership can only move one state at a time, the characteristics of the next higher state become the goals and objective of the capacity-building intervention.

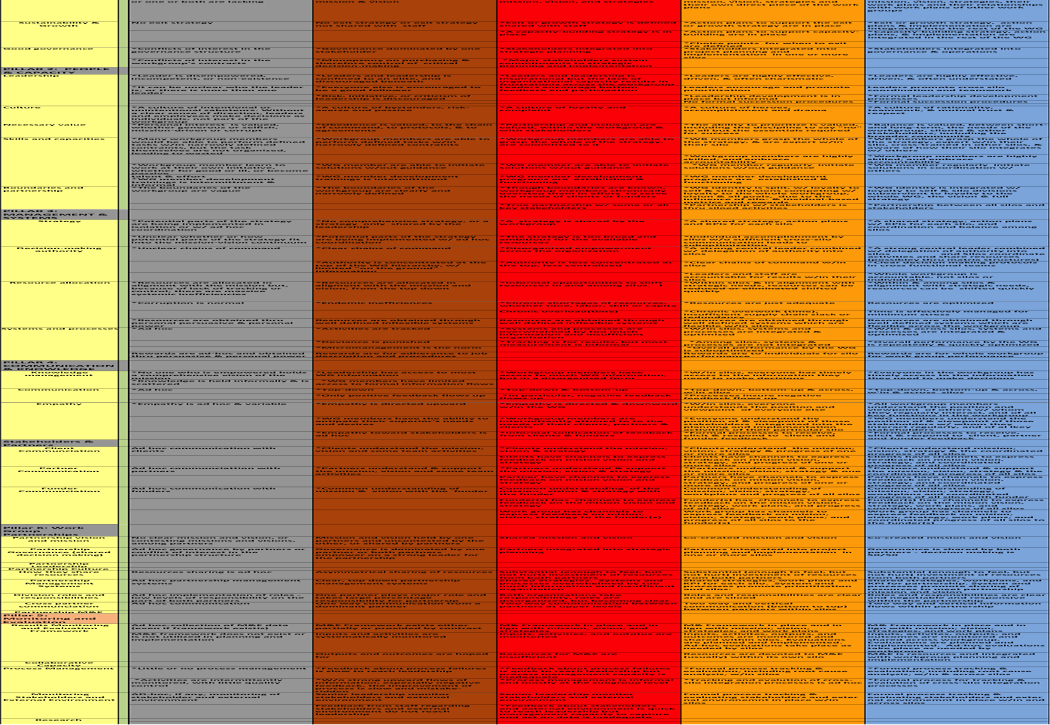

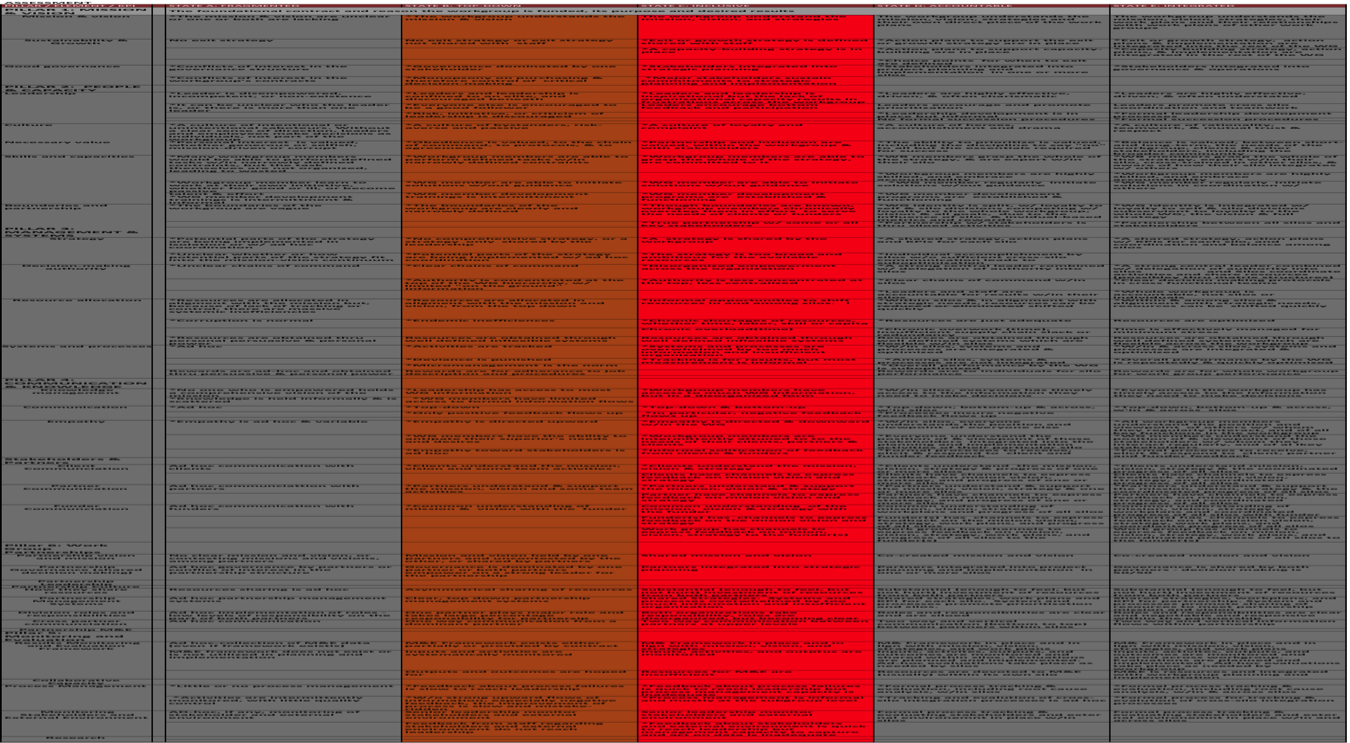

The following graphics show us how the use of a maturity matrix helps refine the design of capacity building efforts. Below is a representation of the cooperative capacity maturity matrix ,which was built over decades of observations and interventions by TWG. Each column contains performance measures arranged by the six pillars. Within this matrix, there are 360 performance measures (such as clear vision and mission), and each one represents a possible intervention to create that performance measure.

Once the cooperative state of the partnership is identified, applying the simple rule that a partnership can only move one state at a time, reduces the number of potential interventions seventy-two (a 75% decrease). Only interventions that will improve each performance measure from the identified state to the next state up are considered. This reduction in potential interventions is depicted in the graphic below. The performance measures in higher and lower states are greyed out, and the interventions needed to achieve those performance measured are not considered at this time (and will not be considered until the partnership moves to a higher cooperative state). In the example below, the matrix identifies only the performance measures relevant for moving a partnership from Top-down to Inclusive.

In this example, only the performance measures required to move this partnership from Top-down to Inclusive are left colored. To move from the Top-down state to the Inclusive State, the partnership will need, in part, to build its capacity to mutually agree on vision, mission, and strategies; create two-way and bottom-up information sharing between partners; and implement systems and practices that respond to the needs of both partners. Trying to directly achieve the performance measures for states higher than Inclusive would be unsuccessful; at best, they would be inefficient and unsustainable, certainly wasteful, and, at worst, counterproductive.

The 72 possible interventions (one for each performance measure) are then further reduced to a maximum of 18, by working with the partnership to identify up to three priority interventions in each of the six pillars.

Finally, these remaining interventions are narrowed to three key initial interventions based on a participatory analysis of:

- Available champions

- Existing blockers

- Available resources

- Current dependencies

- Other constraints

As the first one to three interventions are implemented and the changes established, the capacity building process may proceed with the next one to three priorities identified. During implementation, it is important not to attempt to implement too many interventions at once; doing so will increase stress, promote fragmentation, and thus be counterproductive.

Conclusion

Positive sustainable impact is the goal of development programs worldwide, and requires strong partnerships between client countries’ institutions and outside development actors. To be strong, partnerships require high capacity (skills and systems) to cooperate.

CCP provides a hard, measurable, leading indicator (the Cooperative Capacity State), and metrics (the key performance indicators of the maturity matrix), which enable client countries and outside actors to assess, manage, and strengthen their partnerships. Using CCP’s frameworks, partners can quickly assess the state of their partnership and prioritize, plan, and implement actions to strengthen it.

Incorporating the leading indicators of partnership development into program goals, objectives, and log frames, partners can use partnership development goals to justify the resources and time needed to develop strong and effective partnerships. The results of these improved partnerships will be:

More sustainable development programs, that includes the transfer of skills, processes, budgets, and accountability

- More effective development programs

- Better stakeholder satisfaction for client countries and donor countries

- Better alignment with local, national, and donor programs and objectives

- Competitive advantages for partners vis-à-vis other organizations and countries